"Apollo 13" and the Space Race

The Space Race began on October 4th, 1957, the day the Soviet Union put Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, into outer space. As astronaut Jim Lovell (played by Tom Hanks in Apollo 13) recounted in his book Lost Moon, “The American space program was born not of ambition or passion or celestial wanderlust, but rather of something closer to fear – the fear of being second best. In 1957, the Soviet Union rocked the West with the announcement that it had placed the 184-pound Sputnik satellite into orbit around the Earth. Putting a satellite that weighted 184 pounds into orbit required globe-spanning missiles that packed a propulsive punch of more than 50,000 pounds. The United States had fallen behind the Soviet Union in both the technology game and the propaganda game – if it was going to close the gap, it was going to have to ramp up fast.”

|

| Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to travel in space on April 12, 1961 |

The thought of Sputnik orbiting overhead instilled Americans with a sense of dread and awe, and lent new urgency to the development of rocket technology. When the Soviets followed it up by launching cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin into space four years later in 1961, President Kennedy inaugurated the Apollo program, designed to close the purported “missile gap” between the US and the Soviets while at the same time proving the superiority of American scientific and technological prowess. “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth,” Kennedy announced. “No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space, and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish. But in a very real sense, it will not be one man going to the moon – it will be an entire nation. For all of us must work to put him there.”

|

| Mission Control Flight Chief Gene Kranz during the Apollo 13 mission |

“We were given the opportunity to show what America can do,” said Mission Control Flight Chief Gene Kranz (played by Ed Harris in Apollo 13). “It was almost like President Kennedy grabbed an idea from the 21st century and said, ‘Let’s do it now.’ It might have been more logical to do the space station then, and eventually go to the Moon later in this century. But we really got ahead of ourselves, because we were in a Cold War.”

|

| Apollo 13 astronaut Jim Lovell while training for the mission in 1970 |

Apollo 13 astronaut Jim Lovell joined the space program in 1962, after flying for the Navy in the Korean War and spending four years as a test pilot at the Naval Air Test Center. He was there to witness the very earliest efforts of the Apollo project. “In order to stake their country’s claim in space in the short time they had been given, NASA’s engineers had to develop a whole new type of engineering ethos,” he said. “After 1961, when President Kennedy outrageously promised to put Americans on the moon by 1970, the space agency knew the old way of doing business had to change. There is a thin line between arrogance and confidence, between hubris and true skill, and the engineers and astronauts of NASA spent more than a decade sure-footedly straddling it.”

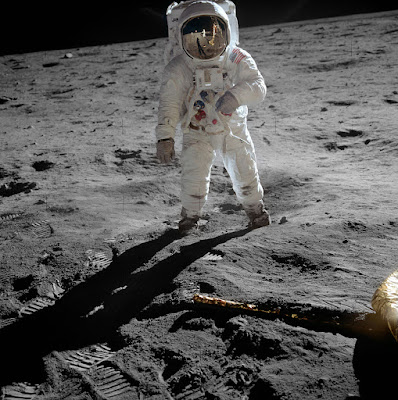

The Apollo project launched nine moon shots in all, over a period of four years. Apollo 8 was a beacon of hope to a troubled nation at the end of 1968 – a year of assassinations, burning cities and political turmoil. The public marveled with the astronauts as they circled the moon ten times, celebrating Christmas in space and watching their first Earthrise over the lifeless lunar horizon. Six months later, on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to walk on the surface of the moon. President Kennedy’s audacious goal had been achieved.

|

| Buzz Aldrin during the Apollo 11 moon landing on July 20, 1969 |

However, by the time Apollo 13 was launched nine months later, the nation’s passion for lunar exploration had grown cold. The Vietnam War – in which nearly 50,000 American soldiers had lost their lives – had escalated into a national nightmare. The Kent State shootings of unarmed students protesting the invasion of Cambodia were less than a month in the future, and the self-assurance with which America had undertaken the Apollo project in 1961 had vanished. Beating the Russians to the moon was a goal of the past, and the public’s eye turned to more pressing matters.

Yet once the Apollo 13 mission was in peril, the space program seized the spotlight once again. Time’s Richard Corliss recalled, “After the explosion, Aquarius became a lifeboat. In it, the astronauts would try sailing home on the gravitational breezes of the moon and the earth. To steer their vessel, they would refute the argument that astronauts were not so much pilots as passengers or cargo – they had to navigate using the sun and the earth as a compass. And with doom dogging their flight, newsfolk and viewers finally paid attention. Imminent death is great for ratings. The Apollo gang got a man on the moon in one urgent decade. Then they worked even more impressively to bring three men back safely from the beyond.”

|

| Mission Control Flight Chief Gene Kranz (in white vest) and the Mission Control team celebrating as Apollo 13 splashed down |

The Space Race officially ended in July 1975 with the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, in which astronauts from the two rival nations rendezvoused in space as part of the policy of détente that the two superpowers were pursuing at the time. It was a great success that led to increased international space cooperation in the decades to come.

After the release of Apollo 13, Time’s Richard Corliss recalled the glory of the space race. “The 17 Apollo moon missions, from 1967 to 1972, provided cubic tons of melodrama, from the explosion of the Apollo 1 test module that killed three astronauts to Neil Armstrong's buoyant lunar stroll from Apollo 11. The apogee of American know-how and teamwork, the program could, at the flick of a wrong switch, careen from triumph to tragedy. In this job, success meant you forged the ultimate frontier; failure meant you died with the whole world watching.”

President John F. Kennedy, “Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs,” May 25, 1961

Jeffrey Kluger and Jim Lovell, Lost Moon, Houghton Mifflin, 1994

John Noble Wilford, “When We Were Racing with the Moon,” New York Times, 6/25/95

Richard Corliss, “Hell of a Ride,” Time, 7/3/95

Anne Lewis, “Apollo Creed,” Austin Chronicle, 1/7/99

Douglas Bailey, “Ex-Flight Chief Recalls ‘Let’s Do It’ Days,” Boston Globe, 4/18/00

Comments